Kimani: You describe yourself as a natural artist. What do you mean by this?

Maddo: It simply means that I received no formal training in art and developed it by scribbling all over the place. But, I do believe that everyone is natural in whatever they do. You must be born with something. School and college’s main task is to sharpen your skills and also assimilate you into society.

Kimani: It is reported that after completing Form 4, your parents enrolled you for an accounting course that you skived and instead wrote to Coastweek asking to do a comic strip for it. Were these early pieces political? What samples did you send to them?

Maddo: Actually, it’s my eldest brother, Ike, who made the attempt to push me to a school of accounts. Little did he know that, at the time, I was secretly working on a comic thriller based on the early 1980s American soap Dallas. I even had my own JR Ewing whom I called ‘LJO’. Book keeping just wasn’t for me. Coastweek asked me to come up with something new, but I still keep the unpublished LJO – produced by a ball-point Bic-pen.

Kimani: Was that your first ever published work? Was it political?

Maddo: No. My very first published work was in the late 1970s, while still in school, when I drew a man ‘thinking’ and sent it to Hilary Ng’weno’s then popular Rainbow magazine for children. I wouldn’t describe it as ‘political’, but maybe the thinking man was contemplating politics. I was famous for a while.

Kimani: What prompted you to choose your career as a cartoonist? Did you always want to be a cartoonist?

Maddo: No. I never really set out to be a cartoonist. You must understand the world then. Drawing cartoons was not considered a career. Understandably so… there was only Edward Gitau’s Juha Kalulu and the occasional Terry Hirst around. I think I stumbled across this business as it were; after Coastweek, I fled from Mombasa to Nairobi and got taken in art-friendly editors, Rashid Mughal and Brian Tetley. I was hooked.

Kimani: Take me through the journey of your life— when & where were you born? Are you the eldest or last born? How many are you in the family?

Maddo: I was born in Jericho, Nairobi, in 1962 and came in a humble fourth in a “clan of six siblings and a pair of parents.”

Kimani: Was the home environment conducive to your choice career? What sort of encouragement did you get in developing your talent?

Maddo: As a kid, my old man tossed us around the country due to the nature of his job. As a result, I only have hazy glimpses of Nairobi’s Eastlands, slightly improved ones of Mombasa, very vivid ones of Kisumu and finally sharp, technicolour images of “shaggs” – my years at Kiboswa in Western Kenya. However, I reckon that it’s against this diverse backdrop that helped model my sense of perception – an important ingredient in the world of art.

Kimani: Where did you go to school?

Maddo: Kisumu (then still only a town) and Nyang’ori in today’s Vihiga County. Most of my former school mates have disappeared, making it very difficult for one to independently verify my having gone to school at all!

Kimani: In your column, you consistently talk of Ondiga. Is he a real life character? Who was he?

Maddo: Ondiga was my playmate in the 1970s at Kiboswa. Without a good education, I found the kid relatively sharp. He attempted to explain things even if his was odd theory. He knew the sun was very big—as big as 10 buses put together. The stars in the night sky weren’t as tiny as they looked, he’d tell me, they were as big as footballs. Ondiga is real and married today with kids. But he doesn’t read a lot, so I can get away with this! My friend Wahome Mutahi (the late “Whispers”) is the one who taught me to use real individuals in humour writing, though, of course, highly dramatized.

Kimani: Another popular aspect of Madd Madd World is the bit dubbed “Twas A Life in Shaggs.” What are some of the memorable thoughts of your life while you were growing up?

Maddo: Today’s youth refer to ‘shaggs’ as ‘ocha’ or something… living in the country side can be very interesting. Right now, I have lived most of my life in the urban world, but memories of yore, don’t go away, so I re-live them in that bit of my column – also inspired by Whispers who’d once in a while take his readers back into time. I also always want to make my younger, more urbanized readers understand that shaggs can be fun too and they shouldn’t be scared of it (though that gecko staring at you in the outhouse is not very easy to deal with).

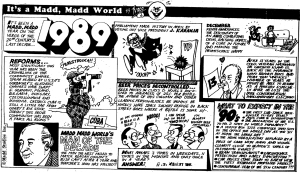

Kimani: Some of your early works includes the famous Pichadithi series. How do you recall this?

Maddo: Pichadithi was a comics series based on folklore and animal tales that was produced jointly by Kul Bahkoo and Terry Hirst. The books were initially illustrated by Hirst who was eventually joined by Frank Odoi who in turn introduced me to the publisher. I only illustrated one. It was a unique series, very African.

Kimani: “It’s a Madd Madd World” is without doubt one of the longest running columns in the country. How have you managed to sustain it for that long?

Maddo: Well, when you have your beer, make sure you go back home to your family, eat, sleep, wake up next day and go to work some more. That’s what I tell folks. You must be dedicated, highly disciplined and have total faith in what you are doing. Believe in yourself, in your dreams. Have the strong desire and ambition to excel, to make a mark, to come out different. There is a very thin line that separates sanity and hopelessness. I have seen many artists give up and end up badly.

Kimani: Some of your earlier characters include Babu Jo and Miguel Sede. What happened to them?

Maddo: Babu Jo was a single-deck, three-frame you-must-laugh-at-the-punchline kind of affair—An African Andy Capp of sort. To produce this kind of demanding piece on a daily basis, an artist needs to be focused on it. I was doing too many things at that time and eventually the character became a bore. My editor then— (Wangethi Mwangi at the Daily Nation) and I agreed to quietly retire Babu Jo. On the other hand, Miguel Sede was a fellow I enjoyed creating. The series was real life, akin to Modesty Blaise and Garth, pretty much my original style (remember I told you about LJO). Sede was an investigative journalist who busted crooked business people and politicians. The series ran in the Sunday Standard but was dropped in a decade ago due to lack of space. So I was told.

Kimani: Any chance the two— Babu Jo and Miguel Sede, will be revived?

Maddo: I doubt it. I am past that ‘golden decade’ when artists have the energy to create new stuff. I am in that category that corresponds with very good wine.

Kimani: You were the first to caricature the former President arap Moi when things were really tough for the media and those clamoring for reforms in Kenya. Was it a gamble you were taking?

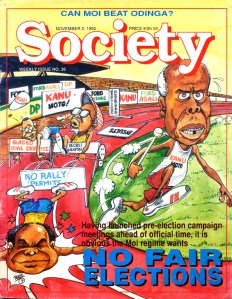

Maddo: Let’s set the record straight. I wasn’t the first to cast Mr. Moi as a cartoon character. University of Nairobi students beat me to it in the early ’80s, albeit their graffiti did not go beyond the pedestrian tunnel near the campus. My cartoon of Moi was the first to be openly published. Yes, it was a gamble worth taking. The editor, Pius Nyamora, at Society which published the cartoon, and I were in agreement that we should test the waters. It was elaborate, full colour and bang on the cover, accusing Moi of being unfair to his 1992 polls opponents by putting hurdles in their way. One of them is President Kibaki.

The magazine used to hit the streets on Mondays. This edition arrived to the sheer excitement of some and utter shock of others. Some people were apprehensive about purchasing a copy for one could be arrested for carrying a “seditious publication”. That day, Nyamora – who had been petrol bombed before – didn’t turn up in the office. I waited patiently at the Standard’s offices on Likoni Road. Nothing. There wasn’t a ranting Moi or a chorus of condemnation from his lieutenants and no state security agents seeking out the editor, his cartoonist and printer. Neither did the agents go around buying all the copies like they had done before with publication they considered to have acrid content.

What was on my mind as I painted that cartoon was that we were on the threshold of a Moi’s final years of absolute political control (I was so convinced that he’s lose at the first multi-party polls). If I was locked up, it wouldn’t be long before I was free again. But, I also considered the other side; I had tried to convince my editor at the Standard, Ali Hafidh that we could start caricaturing the hitherto untouchable elements of the Kanu regime, but he would hear none of it. I did, however, slowly introduce Moi into my editorial cartoons under disguise. I had always figured out one thing; maybe Moi was not all that overly hostile cartoons. The stumbling blocks were editors and Moi’s cronies who probably blacked out critical stories in a newspaper before giving it to him!

Having survived that Monday, the media, Kenyans and Kanu knew that Moi could be depicted in a cartoon. Daily Nation’s Gado, freshly on the job, took cue and went on to produce some of the most stinging cartoons on the then president.

Kimani: As an editorial cartoonist, you were expected to give your graphic commentaries of the goings on in the country in those dark and oppressive days of single party rule. How do you recall those days?

Maddo: Compared to today, we’re a universe apart. As a young cartoonist with fire burning inside me, I really wanted to splutter out all over the place what was in my mind, but of course not much would have gotten past the editors of the time. Besides, one had to be extremely careful too. I tried to be cunning and hide some messages in my work in an effort to beat the editor first and the state agent second.

We were sent copies of the “seditious” Mwakenya publication by Special Branch agents who’d then gauge one’s reaction; if you kept quiet, they knew you were “sympathetic” to the “dissidents”. Whispers was grabbed from right under our noses at Old Nation House.

Kimani: With Madd Madd World, you have continued to hit at the political class using the editorial cartoons and the popular. How has this been taken by the politicians?

Maddo: Politicians have continued to notice my work more and more. Some respect it, others pour scorn on it. I cherish both opinions. Incredulously, while we cartoonists struggled to bash politicians in the Kanu era, we’ve found criticizing today’s political leaders tricky because they always rush to court. It’s a bit like they are the ones who are supposed to be the sole beneficiaries of today’s freedoms. They have discovered that they can sue. Kenya’s media along with civil society was at the forefront of fighting for reforms. The ruling class – which is largely a disguised Kanu, wants to deny this.

There is no different between politicians from both the ruling and opposition side the divide? The latter, in the current political arrangement running the country, hardly exist. There is one big Government with both crammed inside.

Kimani: What are some of the challenges and trials that you encountered while trying to grow your trade?

Maddo: There have been numerous challenges along the long road of change. From the days of Kanu’s intimidation of the media to the current scorn I have mentioned.

Kimani: Please give me an outline of the body of your works – the things that you have done – both in Africa and internationally.

Maddo: I am known for my weekly column. But over the past almost 20 years I have also edited a couple of magazines, all of them short-lived. My colleagues and I faced stiff challenges in that area. Publishing in Africa is still pretty hostile to the small entrepreneur; one must have a few millions to toss down the drain as a publication stabilizes and gains the trust of readers and advertisers.

I have exhibited my work extensively at various venues in Nairobi, Dar es Salaam and Finland. I have once been arm-twisted into teaching an art class at Alliance Française together with my colleague Frank Odoi. I have been interviewed by almost all local TV and radio stations, magazines and newspapers along with a handful of mediums outside Kenya; CNN, Japanese TV, a South African newspaper and Time magazine of New York. I have also been invited to address students – from kindergarten kids to university students shouting out spleen-twisting questions. Producing “live” caricatures has always been a nightmare for me, the worst being in Japan (where I had to depict some individuals with slit eyes in a society that depicts itself in Manga comics with larger eyes) and at the Carnivore in Nairobi where I and Gado drew patrons as Steve Muturi, Big Ted and Shabbir Ansari cracked jokes on stage in a show that was the fore runner of the comedy trio of Redykulluss! and eventually Churchill Live.

I am also putting the finishing touches on a compilation of my work covering the past 22 years that I assembled at a hideaway in northern Italy. The books are scheduled for publication very soon.

Kimani: Where do you draw inspiration for your work? Who was your role model in the industry?

Maddo: I am inspired by earth. I love nature and society which I observe keenly and channel into my work. The Spanish artist Romero who drew Peter O’Donnell’s Modesty Blaise greatly influenced me at a very young age. His images were alive. I studied the comic like I’d get a degree out of it. Unfortunately, today I no longer pursue real-life art. Closer home, I gathered plenty from Terry Hirst and Wahome Mutahi. These two nurtured me my second love of producing cartoons.

Kimani: What is your opinion of the comic industry in the Kenyan and the African literary scene in general? What needs to be done to increase the comic industry’s vibrancy?

Maddo: As I have pointed out to you, I have tried my hand in publishing and found it vicious. Kenya is not very receptive to comics. We prefer stand alone cartoons – like the editorial cartoons in our newspapers today from artists such as Gado, Kham, Vicndula and Ozone. Comics have never really been our thing. That is why Pichadithi and later Sasa Sema’s Kiswahili series collapsed beside earlier series such as Terry Hirst’s Joe that never received advertizing support despite being relatively popular. South African publisher Jim Bailey (whom I briefly worked for at Drum) withdrew his comic titles from Kenya at the end of the 1970s as he wasn’t even breaking even. These were the immensely popular photo comics Big Ben, Boom (Fearless Fang) and Lance Spearman. There was a sprinkling of Western comics here too with a fair audience which included the kids series Beano, Dandy, Beezer and Topper along with Asterix, Tin Tin and the irresistible Marvel Comics. Supported by strong Western economies and huge readership bases back home, these are still available in Kenya.

Maybe you are wondering why I say that local comics were popular and yet add that they collapsed. Readership numbers in Kenyan do not necessarily mirror sales. This is because our society is where you will have several individuals reading the same single copy. This coupled with lack of advertising will whip a publication into an early grave. I’ve been there.

It is an uphill task to attempt to revamp the comic book industry here. I shouldn’t sound pessimistic, but let’s face the facts. Besides trying to convince the populace to read more – and I am talking about general reading, books, magazines – the reading world is under assault from on-line based material.

Kimani: Do you think the industry is able to support an artist to live off it?

Maddo: Oh yes. But, very excruciatingly, this industry is small, so you will find only a few lucky personnel in it. We only have five daily newspapers. That translates quickly to only five editorial cartoonists countrywide! We’ve made one small step forward, though. Unlike in the days when one artist would be a socio-political commentator on the editorial page, produce a comic and illustrate features for a newspaper, these days most newspapers have a bank of artists focusing on the style they are comfortable with.

Kimani: Is there hope beyond the occasional illustrations in the newspaper?

Maddo: Yes. Some artists have moved on – some swallowed by the lucrative advertising and marketing world. New technology has also opened up avenues elsewhere; one doesn’t have to be in the newspapers to earn a living. 3D and CGI is big business now and one is OK there if one is a natural artist in the first place. This field now produces animated movies and tones of TV adverts.

Kimani: What is your opinion of the cartoonists in the newsroom?

Maddo: You want me to start talking about other folks? Anyway, I have had a very good relationship with many of them and indeed three are my colleagues in private business set up. I have helped bring up some into the business by using their work in our previous stand alone publications and gaining them exposure. However, just like in any other business, some new entrants arrive hot-blooded like nuts with a “I’m the best” attitude.

Kimani: Would you say there is a favourable market for comics in the Kenya and Africa in general?

Maddo: Sure. As I have pointed out, some comics in the past did have some readership – though not in overwhelming numbers like in the highly literate West. But if one concentrates on Kenya alone, one is cooked. Whatever publication you plane must be able to sell across the continent and even beyond. And that, again, is a very expensive affair. No bank I Nairobi will loan you capital to publish fiction. There is change in that direction, but it will take eons and I am afraid that by then, we won’t be able to convince a kid to read a comic book when he can control 3D characters dashing about on portable 4-inch screens like that of the PSP – PlayStation Palm. Ha. They are expensive today, but so were cellphones 7 years ago.

Kimani: Please give me some highlights of your happiest moments, memorable times; your trying and challenging times.

Maddo: There are plenty there. You might have to wait for my official auto-bio. Anyway, like anyone else, I have had my ups and downs. I have ridden high and have gotten myself trampled upon. I thank God for a beautiful family of two teenage daughters and a son, and their mum whom I have shared 23 years with. We’ve had absolutely good moments together.

I have spent some weeks in an aristocratic palace in Europe… and addressed a pack of university professors. And I have spent some nights in remand prison for throwing the wrong practical joke.

At my age today, my challenges have not lessened. There are things that are bursting out in me, some stuff I want to do for the world but find that the African socio-economic set up can be unfriendly to some African dreams.

Kimani: What are the other things that you like doing when you are not working? What are your hobbies etc.?

Maddo: Well, I am not much of an outdoor fellow though I love it immensely when the opportunity arises. I love travel, driving on open highways. I am a car buff and trying to fulfill my dream of entering a motor rally before I am 90. I socialize a lot – that’s where I get my fodder from. Once in a while, I jump on stage and jam with a band, playing one single, unchanging chord on guitar. The longest I have lasted there has been three minutes, but in a club with everyone high, it sounds like an hour.

Kimani: What are some of the other extraordinary things that have happened to you and also added invaluable experience to your life as an African cartoonist?

Maddo: It’s actually travel and meeting odd folks that have driven me on in my work. There are all sorts of people out there. Some won’t know it when you use them in your work as broad references. On the physical front, I have managed to hobble along in one peace and thank God for it. Maybe you should wait for my book.

Kimani: What kind of music do you listen to?

Maddo: World music. I appreciate anything that’s good and language doesn’t matter. I am drawn to perfect arrangement and acoustic instrumentation. I tend to frown upon highly synthesized pieces. Also, I listen to different music genres according to my mood. I love jazz a lot but I can only cherish it greatly when it’s being performed live or when I am listening to it while working or in some serene surroundings. Otherwise, you’ll most likely find me blasting Lingala and 1980s Motown in my car. I am very choosy when it comes to local hip hop and rap. I certainly don’t mind the guy who takes time to put a number together than the one who wants to rush it in a couple of hours just because he can cut and paste.

I have also followed and studied various African music styles for decades and was exposed to West African hi-life, Afrobeat and their versions of suk and reggae at an early age. And how I wish Indian musicians would churn out what their fathers used to produce in the 1980s!

Kimani,

You got the best out of Maddo. The interview must have lasted a decade! it is like I have talked to him personally. That was elaborate, and good.

Nice Work.

Lucas Kimanthi

Thank you Lucas. I also posed the questions you had sent and I will post his answers. Watch that space.

Good piece Kimani. MADO keep it up. I just wish it would be cheaper soon to produce some of your comic stories for TV. Its an area that is rich but locally still down. Miguel Sede would definitiely be a hit. Looking back, it was storyboarded very well.

Ingolo

Ingolo, that would be great. Miguel Sede would be an awesome TV series. It would be a hit.

Habari!

Sounds good Mzuri sana ,we did a magazine with Maddo ,African Illustrated 3/4 publications before it collapsed it was fun!

He remember that with nostalgia. Thanks for taking time to read the piece.

He remembers that with nostalgia. Ahsante for taking time to read the piece.

Good stuff Kim n’ Maddo… always the mentor! INSPAYAD!

True Gammz, Maddo has been an inspiration for many.

Beautiful piece! You capture so beautifully how so much history is still untold, how so much about Kenya’s trajectory can be reeled out from the life of one public individual. Really good!

I think we have a lot of untold stories in the country. Ope we can all play our small part to help this stories unfold. Looking forward to reading your next novel, God willing.

Great interview with lots of insight.Keep up Kimani, and give us more like that.

Thanks Blaise. I will certainly keep them coming.

Absolutely well done interview and you certainly nailed the Maddo I know and some that I did not know…but pleasantly suprised to know. Now this is journalism as I knew it too! Thank you for a piece that is an excellent read!

Njeri, ahsante sana. Maddo is a legend. I will post part two of this story in a day or two.

AWESOME…………piece kimani wa wanjiru……Maddo is a national treasure there will be no one like him ever

Thanks Muzi. I also asked him the questions that readers had shared and I am processing that. I will post Maddo’s answers here in a day or two. Watch this space and keep reading. Thanks for the support.

Great cartoonist – Great interviewer! I admire you both!

Greetings from Scandinavia!

Mélanie

Thanks Melanie. An honour interviewing a legend like Maddo. and your compliments are much appreciated.

Always enjoyed your quirky interpretation of events, the ability to see that other dimension which others don’t see and of course your madness. Your partnership (in crime) with whispers changed satire in Kenya

Don’t you just love his eyes for some details? Well maybe tis the gift of those protruding eyes….

this is a brilliant piece of writing . you don not only write but capture the spirit of this great visual guru. its a boost in the arm to document the exploits of our artist than that power to foreigners who seem to be quote and quote the instrumentalist of our our stories. maddo has been interviewed by many but this is the first interview that gets it right.

Hey Pato, thanks so much for your kind words. Like you, I believe that we should tell our stories and makers of history. Appreciate it a lot.

Pingback: Kenyan cartoonist, Paul Kelemba, nominated for prestigious CNN Award - Kenya Satellite Network

Great piece to read. Not surprised though, l have known Maddo since High School days at Nyangori whern l was a day scholar and rented a flat from his parents on Kiboswa Market. I found him pretty sharp and creative in many ways.

Whats more…….his elder brother Oliver taught me Chemistry. Kudos to the entire family…..

Eliud Mmata.

USA.